Sometimes, when things in life don't go the way we planned, we blame our children. Sad, but sometimes true.

In the Congo, we discovered an extraordinary tale of what is happening as some adults are taking this sad reality to a frightening extreme. Meet Belinda Kaji Manengu. At only 8 years of age, Belinda should (like other children her age) be enjoying all the carefree fun that life has to offer a child.

Meet Belinda Kaji Manengu. At only 8 years of age, Belinda should (like other children her age) be enjoying all the carefree fun that life has to offer a child.

Instead, her parents both died of AIDS, and she went for a time to live with an uncle. But, angry about his brother's death, her uncle and his family accused Belinda of witchcraft and blamed her for the tragedy.

Unbelievably, this is a fairly common occurrence in the Congo. In Lubumbashi alone -- a major city near the southern border with Zambia, and an area with a relatively high prevalence of HIV thanks to thousands of truck drivers who cross the border every day -- there are an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 children living on the streets, and the majority of these are there because they have been accused of witchraft. The locals here call them "sorcery children."

In Kinshasa, Congo's capital in the west and largest city, the number of street children is estimated at between 25,000 and 30,000, and at least 60% of them are estimated to be on the streets because of a sorcery accusation. Children as young as 5 have been abused or thrown out onto the streets because of a sorcery allegation.

We were told that pastors and churches are sometimes complicit in this tragic practice. Families upset about a misfortune, such as the death of a family member due to AIDS, will consult ill-informed pastors, who -- for a fee -- "diagnose" the root of the problem as a child practicing withcraft. These children are then subjected to a horrific cure -- "exorcism."

In this case, exorcism doesn't mean what you probably think it does. In order to "cure" these children of their supposed inclination to sorcery, they are basically abused -- even tortured.

We were told about one girl whose skin was burned with fire in order to "cast out the demon." And they are even expelled from their homes and left to wander the streets. Fending for themselves and sleeping in public areas such as parks, alleys, or train stations, they become all-too-easy prey for child sex predators. In addition to being victimized by HIV or violence, they also have a high rate of accidents, being struck by vehicles or run over by trains.

And naturally, many simply run away to escape the abuse. We asked the founder of the World Vision-assisted Faradja Center for orphans and vulnerable children, Mrs. Maguy Numbi, 47, how Belinda came to be at the center. "She ran away. After sleeping at the train station and other places for a number of months," she said, "one morning we discovered her sleeping under the window of our office here and took her in."

"And why did you run away?" we asked Belinda.

"I cannot go back to my family," she replied. "I was beaten every day."

The Faradja Center is far too small to house all of the 230 children they are working with. They have one small bedroom with a bunk bed, where nine boys sleep each night -- two to a mattress, and five on the floor. The room is a third the size of most hotel rooms.

As for Belinda, Mrs. Numbi managed to get her placed with another relative who now cares for her and shields her from abuse. With World Vision's help, providing school fees and uniforms and funds for health care, she also works to ensure that the children are placed in local schools so they can resume their education, and gets them regular checkups and urgent medical attention at local clinics. But for the Faradja Center, this daily struggle to get children off the streets is a life and death matter. World Vision assists by providing food for meals and other needs, and the 15 volunteer caregivers who work with the children have all received training from UNICEF. They also employ creative means to pay the rent and purchase more of the food they need; the older girls knit sweaters and other garments by hand and they barter them in the market for the cash and supplies they need to stay afloat.

But for the Faradja Center, this daily struggle to get children off the streets is a life and death matter. World Vision assists by providing food for meals and other needs, and the 15 volunteer caregivers who work with the children have all received training from UNICEF. They also employ creative means to pay the rent and purchase more of the food they need; the older girls knit sweaters and other garments by hand and they barter them in the market for the cash and supplies they need to stay afloat.

They need far more than they have to work with ... more space, more financial resources (every staff member is 100% volunteer, including Mrs. Numbi, who has nine children of her own to feed), more trained volunteers, and simply more capacity to help children. Mrs. Numbi says that every time they venture out into the marketplace or other public places, they find more "sorcery children" who need to be rescued from almost certain victimization on the streets.

Captions: Top photo -- Belinda's eyes betray just a fraction of the tragedy that has thus far marked her young life.

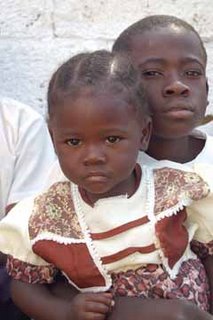

Bottom -- Two more "sorcery children" at the Faradja Center. In addition to all the other struggles these children have to deal with, many of the orphans served by the Center are themselves also HIV-positive, as a result of sexual abuse or vertical transmission from infected mothers (in utero or sometimes due to breastfeeding).

More Info on Sorcery Children -- April 2006 Human Rights Watch report highlighted by BBC News, Worldwide Religious News, and ReliefWeb.

"They say I ate my father. But I didn't." Los Angeles Times, August 29, 2006.

Watchlist Report on child trafficking and exploitation in the Congo

U.S. State Department information on sorcery as a religious practice in the DRC.

Congolese blame Ebola deaths on "sorcery"

IRIN News: NGOs, public authorities denounce killings of suspected "sorcerers" in the Congo

Wikipedia article on how indigenous beliefs in sorcery intersect with Christian faith in the Congo

March 2004 New Humanist article on the torture of child "sorcerers" in the Congo

May 2002 Global Action on Aging article about how sorcery is used as an excuse to abandon the elderly in the Congo

Information about shelters offered by the Catholic Church in the Congo for children and the elderly accused of sorcery and expelled

Friday, July 07, 2006

"Sorcery Children"

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

God bless you in your work and thank you for starting this blog.

Post a Comment